A Dialogue

With Katerra

by Craig Curtis

FAIA, Design Director, Katerra

Craig Curtis speaks on supply chains, scale, platforms and mass customization in a design-quality-focused organization

DesignIntelligence (DI): Katerra has a rare position in the A/E/C marketplace as a vertically integrated company. Yet your background had been in traditional architectural practice. Can you share your background, how you got here, and your current role at Katerra?

Craig Curtis (CC:) I spent most of my career at the Miller Hull partnership. I joined the firm in 1987 after spending a few years down in California after university. I was there from ‘87 for almost 30 years. It was a fantastic experience. Dave Miller, Bob Hull, Norman Strong, and I were the four partners for quite a few years. The firm grew and I led the charge to open an office in San Diego for the firm. I had some incredible commissions there – a worldwide U.S. Embassy contract and a GSA land port of entry at San Ysidro, the busiest border crossing in the world, and the largest GSA project at that time. That kept our firm afloat through the recession. I was fortunate to be in that position and to work alongside Dave Miller and Bob Hull, my mentors for 30 years. A fantastic experience and a great run. We grew the firm from 8 when I started to close to a hundred when I left. Nice steady growth with a deep bunch of talented people - which is what you need to do high-profile work.

At Miller Hull I had hired a guy out of college named Peter Wolff. Peter was one of the Wolff brothers in a family-owned Multifamily development business in Spokane. He was the lone architect/designer of the family. He wanted to go into architecture and bring higher design to his family business.

After several years at Miller Hull he went back to work for his family developing Multifamily apartments. We remained friends for years and did projects together. Both when he was at Miller Hull and later, when I designed a couple projects for him when he was back at his family business. In 2015 he told me about Katerra. I could tell he was excited about it. More passionate than I’d seen him in a long time. At the same time, I was at that point in my career, 55 years old, thinking, do I just want to coast into the sunset at Miller Hull and not try anything else in my career? I’ve got at least a good 10, 15 years left. Do I want to try something else?

Pete convinced me to go to work part-time with him and launch the Katerra design office in Seattle, starting part time. I quickly realized there was nothing part time about Katerra. It was full time and more. In January 2016, I severed my ties with Miller Hull and went full Katerra. It was a nice long transition. I gave my partners plenty of time, six months of transitioning out. No hard feelings or any hardship put on that office when I left.

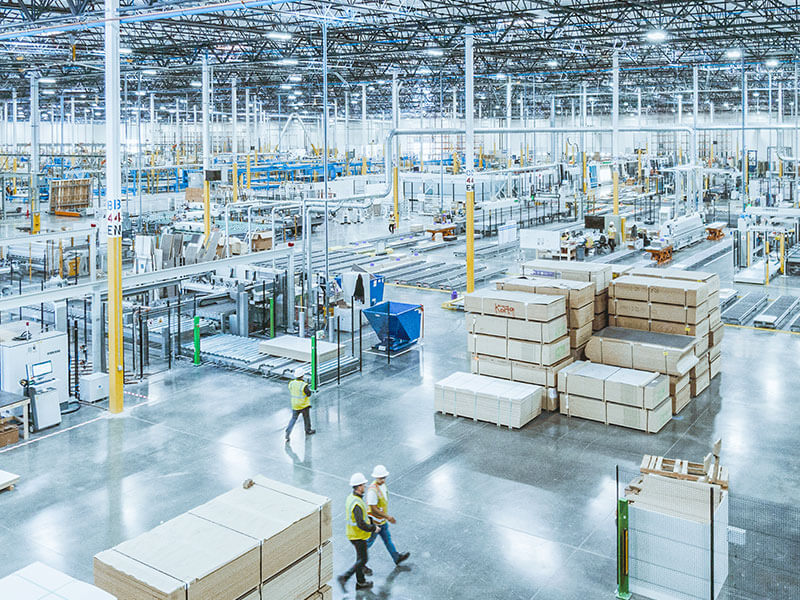

I joined Pete and we opened the design office of Katerra in January 2016. I recruited another ex-Miller Hull guy who was at Olson Kundig, Will Caramella. Pete brought along another young industrial designer he was working with named Will Root. The four of us started Katerra’s design arm. The company was only about 40 people worldwide, primarily a supply chain company in those days. We realized the company needed to have construction, manufacturing, and in-house design capabilities to accomplish the vision.

DI: It existed as a supply chain and manufacturing company first?

CC: Yes. It started because Michael Marks, our founder and CEO, was friends with Fritz Wolff, one of the brothers of the Wolff company, a successful Multifamily developer. Michael had been in the consumer electronics business and had been an entrepreneur. He and Fritz started talking about Fritz’s business and Michael said: “Well, you must get a great deal on things like drywall or doors because you can aggregate that demand across all of your projects.”

Fritz said, “No, that’s not how this business works. We have different contractors, they have different subs, they have different suppliers who take them fishing every summer. There’s no way of controlling where I’m going to get my doors, windows, and flooring. Even if I specify it, there’s no guarantee until the end.” Michael was shocked. “That’s not how the rest of the world works. How can that possibly be the case?” he said. He volunteered to help Fritz put together a supply chain for Wolff’s Multifamily projects, and quickly found he could, in fact, get a much better deal on materials.

What he couldn’t control was those subcontractors and suppliers all the way up the multiple steps to general contractor. Work had to be specified into the project in order to get it. He had to go all the way back to the design team. They quickly understood to be successful you have to be in control of the entire process from design all the way through installation and occupancy. From there, my role now is as Director of Design.

DI: That notion of supply chain control was part of the founding vision, the initial charter?

CC: Absolutely.

DI: Katerra has made several big splashes in recent years for acquisitions. Is growth by acquisition a key strategy to achieve scale?

CC: I get asked that question a lot. But I like to remind people of the size of the industry. It’s massive. Even though we fully intend to have an impact at scale, we can’t do it simply by buying a bunch of firms. In fact, we’ve only made three acquisitions.

One was a very small firm in Spokane and then we made two more significant acquisitions almost three years ago. We have made no design firm acquisitions since, nor do I think we need to, because those were very strategic. We fit with Michael Green because of the Mass Timber expertise he brought, along with Equilibrium. That was a no brainer because we we’re going into the Mass Timber business in a big way. We acquired Lord Aeck Sargent for two reasons. Geographically, they provide us with six offices with good locations and a design headquarters in Atlanta, a perfect place for us to have a second design headquarters. Secondly, they have a deep bunch of talent. A firm that’s been around for probably 75 years now. As mentioned before, to do high caliber work you need high caliber people.

The people there are very, high quality. Processes are in place we can learn from. In the long run that’s going to prove to be a smart partnership. I think of it more as a partnership than an acquisition. They got in with Katerra when we were in our infancy in terms of design capabilities.

DI: Talk more about size. Will there continue to be a place in the industry for the small firm?

CC: While we offer every product and service needed to deliver building projects, the industry is large and there is a place for firms of all sizes. Our focus is on designing and building platforms. My dream is that they become accessible for anyone to be able to use. That puts some of the information about costs, schedule, and other data - and the attendant power it brings - back into the hands of the architect. I know you’ve operated as both architect and within the office of a general contractor. I saw the reference to you as a “dual agent.”

We’re trying to get to the point where we’re working together side by side with the builder with equal access to that information. If we’re providing platforms anyone can use, anyone could buy one of our bath kits, for example. In the future, I would hope that people would be designing single family homes using our assemblies and being as creative as they want to be, but with access to all that information. It’s pre-engineered. The supply chain and the catalog of materials is top notch because everything we do is high-quality design. Most importantly, we can provide you with the cost of those manufactured assemblies. You know, as an architect or designer, what cost to plug into a project. You don’t have to wait for a bid from the contractor who has to go out to subs who have to go to suppliers to get the actual number. That’s all baked into our manufacturing assembly. It’s coming out of our factory, not out of somebody’s pickup truck.

DI: That’s interesting and it goes against my preconceptions, which were: “Katerra is interested in continued acquisitions, global dominance, trying to be the biggest.” What I’m hearing you saying is: not necessarily so. You just want to have more control of what you’re doing.

CC: The answer is to scale. If you think about scaling a platform, for example, how did Uber scale? They didn’t scale by growing a massive number of people back in the home office. They scaled through a platform approach. Alibaba is probably the best example of how a platform approach can work at a large scale. We could do the same thing. Sure, we can have a major impact at scale, but we don’t have to do it by acquisition and by having thousands of architects. We can have maybe a few hundred architects who are providing all the information needed for other architects, who build and use that information to build smarter, to build more efficiently, less expensively and solve some of these social issues.

The reason I’m here is to try to make a difference in providing affordable high-quality workforce housing. Also, a means to utilize mass timber more effectively and promote that as a way to make a difference in climate change. Those two things are important and are two of the biggest challenges that architects have to face right now. Katerra has a good shot at having an impact on both. Sustainability is extremely important to us.

DI: As a lifelong architect at heart, the notions of platform and scale are not household words to me. To hear you talking about that rather than dominance and acquisition is more graspable. I can get my arms around it. We share that aspiration, even though we came at it in different ways. What we have in common is being two career architects who couldn’t take the status quo anymore - and did something about it – by making a significant career pivot.

I’m thrilled you had that courage and are now an exemplar for others. What drew you to your current role? Was there an aspect of practicing within a traditional firm that destined you for such a change? Were you a designer, a production guy, a manager? What gave the impetus to want to be in this role? What drove you here?

CC: When I look back at even the top commissions I had as a lead designer, say U.S. Embassies worldwide, that’s as good as it gets. Even with those projects - and they were design-build projects - you would think in a program like that, that had been around for so long that we would be effective at managing the design-build process. That it would be collaborative and enjoyable. But it wasn’t. In 30 years, I can look back and point at fantastic accomplishments architecturally but there are only a handful where I could say it was an enjoyable process through construction. There’s so much angst, and so many battles to fight around the cost of a project versus design quality.

That’s what I got tired of. To have an opportunity to join something and think about a completely new way of delivering a project without all that baggage and banging your head against the wall constantly. The same old battles over and over. That’s what was most interesting to me. When I joined, I had no idea that Katerra would become what it is today, on our path to becoming what our vision is for this company. It’s fantastic. I’m thrilled about it. But when I joined it was very small, just an idea and we didn’t know this is where it was going to head.

I have loved being part of growing the design organization and learning about how almost every other industry in the world is run. Much differently than design and construction. It’s really been eye opening. I’ve learned so much and I’ve met so many people from outside the industry who are running this company in a way I couldn’t have imagined when I was working for a boutique design firm.

DI: Most firms in traditional design practice don’t give much attention to the notion of supply chain. They’re self-focused. Architects are educated and cultured that way. We’re lucky if we even remember to call our consulting engineers and God forbid - the subcontractors and contractors and manufacturers, who are often seen as “second-and-third-class citizens.” You obviously embraced going about that in a new way.

What are some of the advantages of the integrated approach to design, construction, manufacturing, and supply chain you’re using? What are some of the synergies, unexpected consequences, and challenges?

CC: Designing for platforms instead of individual projects is a new way to think about practicing. We’re designing for entire platforms. For example, our Multifamily platform has a catalog of materials. The advantage is we can curate that catalog specifically to who we want to be, just as Apple has a distinctive look for all their products. If you’re buying a phone, a laptop or whatever. Whatever product you’re buying from Apple, you know it’s going to have that certain look. That’s been very successful for them. It’s widely recognized as one of the best designed product lines out there. That’s essentially what we want to be.

We want to have a fine catalog of products we’ve fully vetted that meet our standards, not only for aesthetics, but for sustainability, longevity, warranty and all those things. We build our platforms around that, which is quite a different way to think about designing.

DI: Has the COVID-19 crisis had an impact on your supply chain?

CC: There has been very little impact. Part of the reason is we have a diversified supply chain. The recent trade war pushed us to make sure we’ve always got back up plans for every one of our products.

We’re well diversified geographically. We’ve got nearly a hundred people in the company involved in supply chain and they’re all over the globe. The advantage to a company like ourselves is because we have in- house all those people canvassing the globe for our products, we can react very quickly to a crisis like this. We’re not tied to one particular manufacturer, or one location. We have lots of options.

DI: The benefits of what you’re talking are clear for an integrated company like yours. What about firms not in a position to control their own supply chain. Are there some principles that could apply to a design only or a construction only firm? To share with those who can’t go your route?

CC: That’s a tough one for me to answer. It’s been a while since I’ve operated within just a strict design firm. I’m not sure how this would impact a firm like Miller Hull, for example. But the beauty of Katerra’s supply chain is that it’s accessible to the whole industry—any architect or GC can reap its benefits.

DI: Having made the transition from strict design to supply-chain-focused scale and platform design, have you ever crossed over to the “dark side” where you’ve said, “Oh my God, I got what I wanted and now it’s oppressive. Now I’m a factory guy. I’m a manufacturing guy. Where did the creativity go?”

CC: Not at all. Designing at platform scale is challenging and creative. I thought doing a project under the GSA Federal Design Excellence program was difficult. Designing a platform that can be rolled out and provide design excellence over multiple buildings and still provide mass customization is an order of magnitude harder. We have a lot of talented architects here at Katerra. All are surprised and humbled by how difficult it is to design in this way. Because we’re not about the lowest cost solution or lowest denominator. We’re about providing design excellence in a new way and still providing the kind of flexibility in our platforms that allows for fantastic architecture.

Mass Timber is going to be a big part of everything we do in the future. That alone leads to some beautiful new ways of thinking about design. That’s a technology we’re going to see more and more of over the next decades. I can’t wait to see the award-winning architecture that Mass Timber provides.

DI: That’s exciting. All I’ve ever attempted to do is to be systematic within a given project. To take that across a global supply chain organization long term, I imagine, requires lots of talented people to help. I can only imagine what the struggles and challenges would be.

CC: Coming out of COVID-19 there’s going to be a heightened awareness on healthy buildings, well buildings, biophilic design and environmental responsibility. Maybe one good thing that will come out of this is that people will care more about the health and wellbeing of the people who work in their buildings. I hope we can use this to make sure we think hard about providing healthy building materials and wonderful places for people to work. Whether you’re in a home office or in a commercial office building, I think we’ll see more attention to it.

DI: I hope so. Plenty of others in the industry can benefit from those things already baked into the Katerra culture and value set.

Craig Curtis, FAIA, is chief architect at Katerra where he oversees new building platforms while ensuring they meet and exceed sustainability goals. Craig was a partner with The Miller Hull Partnership for 30 years before joining the Katerra team. Craig’s projects at Miller Hull included the Bullitt Center, the world’s first commercial office building to meet the stringent requirements of the Living Building Challenge, and the $450m replacement of the San Ysidro Land Port of Entry, the busiest border crossing in the world. Craig’s success with the design of many award-winning projects was possible because of his integrated design approach: relying heavily on his team of architects, engineers, and contractors to solve complicated problems simply, creatively and elegantly, together.