Cross-Disciplinary Research

to Reshape the Built Environment

BARBARA BRYSON

Associate Dean for Research, College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona

As Associate Dean for Research in the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona, Barbara Bryson has spent years examining the importance of research in the built environment. She recently spearheaded a university-wide multi-disciplinary strategic initiative and symposium on research in the built environment at the university called “RESTRUCT.” She spoke to DesignIntelligence about this initiative, and how the design, construction and ownership communities can use research to build for the future.

DesignIntelligence (DI): Your passion and advocacy for the emergence of research in the design, construction and ownership professions seem to be at a peak level as we begin the year. What forces are driving that? Why now?

Barbara Bryson (BB): There are many reasons for believing research in the built environment is extraordinarily important right now. Almost nothing impacts our health, our economy, our culture, our well-being, our resources, or our climate quite as much as our built environment does. Yet, the amount of research that has been done, in a holistic fashion, to solve the challenges of the built environment is almost minuscule compared to other areas of research.

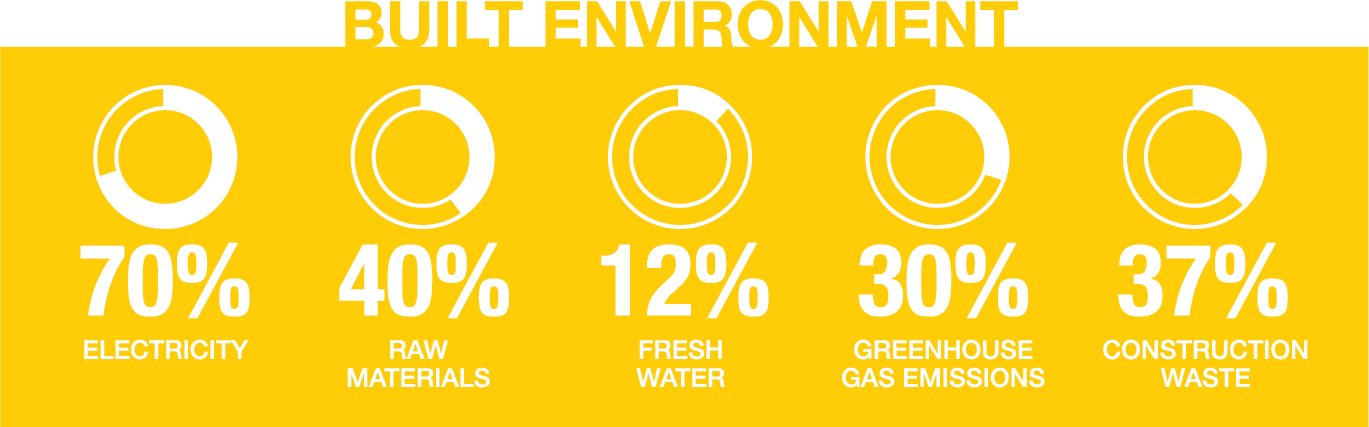

According to the U.S. Green Building Council, in 2005, 70% of the electricity in the United States was consumed by our built environment. Edmondson and Reynolds wrote in “Building the Future” that 40% of raw materials and 12% of fresh water go into our built environment. Many sources tell us 30% or more of greenhouse gas emissions are generated by the built environment. A McKinsey report told us we have the opportunity to save $700 billion a year by addressing energy efficiency in the built environment. According to the Technology Strategy Board in the United Kingdom, 45% of the U.K.’s total carbon emissions are generated by buildings. The Movement for Innovation Industry Report, published by The Economist in 2002, stated that 37% of construction materials are wasted. In Hong Kong, they estimated 38% of the total waste from their region comes from construction sites. Nearly every article on our cities and environment contain data related to impact and opportunities of the built environment.

Not all the data is environmentally driven. According to economists in 2017, 60% of the buildings in the U.K. failed to meet schedule goals, and 90% of the world’s infrastructure problems do not meet budget or schedule goals. Edmondson and Reynolds also wrote in “Building the Future” that 75% of the activities in construction add no value, and, if we in the design and construction industry were as efficient as the manufacturing industry, we would add $1.6 trillion to the world economy. The ASCE estimates the U.S. needs to spend $4.5 trillion by 2025 to fix the country’s roads, bridges, dams and other infrastructure, and that we have around 25,000 structurally deficient bridges.

Those aren’t just environmental concerns, those are also economic, quality of life and efficiency concerns. For years, research into the built environment has been either neglected entirely or has been the purview of only the usual suspects. It’s time to look at how research can be addressed in buildings, so we solve these problems in a way that is fully informed, impacts decisions, and shapes policy.

DI: What was your intent in convening the RESTRUCT (RESTRUCT.arizona.edu) symposium around research? Who was invited? What were your goals?

BB: First, it wasn’t just me. Almost two years ago, the new dean of the University of Arizona College of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture, Dean Nancy Pollock-Ellwand, initiated a strategic planning process for the college. During that process, we had several focus areas, and one was research. The research working group, which I was a part of, looked at how we could improve and enhance research efforts at the college. We identified the problems I mentioned and realized they were larger than just our three disciplines, architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning.

We decided to further the discussion and talk to the university as a whole. The new president, Dr. Robert Robbins, was going through his own strategic planning process. We approached the strategic planning team with the idea that the University of Arizona could be the first to develop a robust university-wide ecosystem supporting research, teaching and service for the built environment, defining new, fully integrated discipline-leveraging knowledge and research from all the university colleges. We imagined - through a process of workshops and symposiums - we would be able to focus on discussions that might include livable cities, the trillion-sensor future, crisis response, technology, changing design processes, decision policies, and built environment life cycles.

The university’s strategic planning team embraced the idea and funded steps to begin these conversations. The symposium we held on December 12, 2019, was the culmination of a yearlong set of conversations, planning activities, and faculty workshops defining the grand challenges that the university would be taking on. The following day, we held an industry workshop, in which we had 30 industry participants from all over the country tell us what they thought about the work we were doing and how they might like to be engaged in that work. The goal was to create an understanding of how industry and the university could align on building knowledge.

We named the event RESTRUCT, but that is not just the name of the event, it’s the name of the entire initiative. After all, as our team has stated, “We are living the consequences of our standard practice. It is time to rethink, redefine, redesign, and restruct our human environment.” We are doing just that through transdisciplinary research.

We invited the community, faculty, students, and industry members to the RESTRUCT symposium. It was great to have industry members come to what are essentially academic presentations. What I wanted our civic and industry partners to understand above all was what rigorous research really is and how difficult it is. It’s challenging to develop knowledge in a way that is credible, peer-reviewed, and replicable. In short, knowledge built in a manner that builds confidence. I hope the industry community will understand how the convergence of researchers with differing perspectives can change the questions, change how we think about decision-making, change how we think about processes of designing, change policy, and change how we deliver the built environment.

DI: You mentioned the university developed grand challenges to take on in addition to creating the symposium. What are they?

BB: The University of Arizona is focusing on four grand challenges of the built environment. These aren’t the only grand challenges out there, and we’re hoping other universities follow our model. The four grand challenges the university has selected are:

First, “redress inequality/injustice in re-envisioning the built environment.” That means re-addressing inequality and injustice through thinking about access to infrastructure such as utilities and internet and providing equitable interior urban spaces to meet basic human conditions. This is the area in which you would address accessibility and connectedness.

The second grand challenge is “creating resilient and efficient urban and rural systems.” This goes to our strengths in environmental studies and in climate studies, but we also need to redesign systems for a more resilient future, designing the built environment to adapt and mitigate climate change, creating efficient urban food systems, and address crisis response. We also need to look at systems that achieve net-zero resource consumption in the built environment, decarbonization, and dematerialization.

The third grand challenge, “design for optimal health”, also builds on the strength of our Health Sciences program; in fact, the Health Sciences program has also adopted the built environment as one of their grand challenges. “Design for optimal health” means we’re linking health, wellness and social interactions to the built environment. How do we design operations to address major health needs across age, disability and occupation? How do we design human-machine interfacing to optimize work efficiency and human health, aging with human dignity, and designing for health in an increasingly extreme environment?

Finally, the fourth grand challenge is “enabling innovation through better decision-making and data analysis.” For us, this means creating decision support that effectively integrates public values and scientific information. This challenge addresses interdisciplinary mixed-method, data-driven evaluation to foster innovation in the built environment. It also promotes evidence-based governance and leveraging big data analytics for decision-making.

At the university-level, research is built on individuals and then on teams with common interests. For example, we have a team interested in crisis response in disadvantaged areas, that includes people from health sciences and people from our data sciences or atmospheric sciences, engineering, law, social and behavioral sciences — the work goes across the disciplinary boundaries to answer these big questions. We have construction management in our engineering college. They will be using some of these big-data analytics for decision-making to support work they may be doing in delivery processes.

DI: The symposium name, “RESTRUCT,” suggests there was discussion on project delivery methods, structures, and new ways to form teams and execute projects in research-based ways. Is this true?

BB: I’m writing a book called “Creating a Culture of Predictable Outcomes.” In it, I discuss that we’ve been asking the wrong questions related to project delivery for a long time. As an example, I am often asked: What is the right delivery process? My response is: That’s not the right question.

Process and delivery methods impact what you do, how you do it, and how well you do it. But the impactful questions are much higher level than that. How do we work together? Successful projects with predictable outcomes are products of three things: leadership, collaboration and decision-making. Leadership empowers teams, motivates teams and places the right people on the teams, because high-performance collaboration works in the right way, values diversity and makes sure the best idea wins. This creates an environment where people can speak their mind and get the right information out there. Decision-making discipline gathers the right knowledge and make sure decisions are informed. Once all these elements are in place you can move into an innovative environment where real disruption — real innovation — can occur.

DI: What do you see as the first steps or leverage points in turning this into action — for the industry, for the government and for the design community as a whole?

BB: For those of us who’ve been long involved in the process of building buildings, how many times have we pushed away people who have tried to give us input about what we’re building and how we’re building because we thought of them as outsiders to the process?

Yet they are absolutely part of the stakeholder group. Deeply involved — and deeply impacted — by decisions we have made. I think about it as a person who formerly led the building program on a university campus. Everything we put on the edge of our campus changed the neighborhood dynamic just outside the edge of campus. We, as builders, planners, owners and implementers of the built environment must recognize there are many people who should have a voice in what we’re doing. We also get frustrated when we want something done but don’t know how to get it done because we don’t know how to implement policy in city government. Yet we don’t pull in the behavioral scientists, business scholars or legal scholars to help us understand how all these systems work. That’s why this strategic initiative in built environment research by the University of Arizona — so inclusive of other disciplines — is so important.

DI: What’s your advice for firms around the country who want to take action? Firms looking to join or build on what you are discussing here?

BB: They should start by asking questions about what they’re doing. What about their work would be better if they had credible knowledge that informed some aspect of their work? How would their work be improved? It might be a practice they are regularly incorporating into their work, but they are not confident it’s the right decision because they don’t have credible evidence it is the right thing to do.

As an example, Stephanie Carlisle at KieranTimberlake, just published a wonderful article in Fast Company. She writes, “I’ve been polluting the planet for years. I’m not an oil exec, I’m an architect.” You can tell Carlisle is asking herself some hard questions about her ordinary practices as an architect.

Once you have a list of questions, then go to your local university and have a conversation with the chair of the architecture department or someone in engineering and see if resources are available, or if there is somebody there also interested in those questions. Through an initial conversation, you might be able to work together to find those answers.

DI: What question am I not asking that needs to be asked? That you want me to ask? The question nobody’s asking that will have the greatest impact in advancing a smarter built environment industry?

BB: The question not being asked is this: How would 20 freight trains of disruption change all this? I think the 20 freight trains of disruption — AI, machine learning, robotic construction, prefabrication, property technology, trillion-sensor future, all the different trends that aren’t even just trends anymore — are going to drive the need for more knowledge-building and knowledge-creation. They are going to drive your need as an architect, engineer, construction manager or project manager to have resources for knowledge. So, thinking about it proactively, how you want to build or define those resources in the future is going to be incredibly important. Get ready, because the disruption is already here.

We need to have a general understanding in the industry that building knowledge is not only welcome, it’s critical. We need to be working together to share data and information, then build and share that knowledge. We are so far behind in our industry, if we don’t get better at what we’re doing by sharing knowledge, somebody else is going to do it for us.