Beyond Buildings … to Well-Being

by Paul Hyett

Past President, RIBA, Hon FAIA

Vickery Hyett Architects, Founder—Partner

August 31, 2022

Paul Hyett examines the responsibilities of place-making and world building on human development — at two scales

Governmental Leadership

In the post-World War II United Kingdom, a combination of overcrowding, damage from the bombing raids and decades of inadequate maintenance generated dreadful problems of dilapidation and distress within the poor-quality Victorian housing and tenements. An ambitious Labour government thus embarked on a major programme of slum clearance and municipal home building as part of an overall vision. Drawing on the Beveridge Report of 1942, it planned a welfare state that would “insure people from cradle to grave.” This blueprint for the creation of a New Jerusalem became a national phenomenon: Following the brutality and destruction of war, here was world building at its most benign and generous — a prosperous yet egalitarian society for all.

Much of the heavy demand for those new municipal homes would be met through prefabrication. The factories that had been heavily engaged in armament and ammunition production were thus turned over to the systemised manufacture of buildings, marking a purposeful transition from destruction to construction. Sadly, this transition also marked the beginning of another major assault on traditional trade and craft skills within the building industry, but that is another story.

The so-called Cornish Unit (named after its supplier) was one of the most common of the “pre-fabs” of the era. It was available in two basic designs. Type 2 offered white precast concrete panels for the entirety of its external walling. That was radical enough. But Type 1, with its combination of concrete panelling and a mansard roof that covered the upper floor, offered a completely new and distinctive appearance that broke with all traditional housing aesthetics.

However, modern as they may have looked, and exceptionally generous as their space standards were, poor thermal insulation and problems such as condensation led to the widespread condemnation and frequent demolition of Cornish Units during the ‘80s. But many units survived to be sold off by the municipalities to private homeowners.

Family Matters

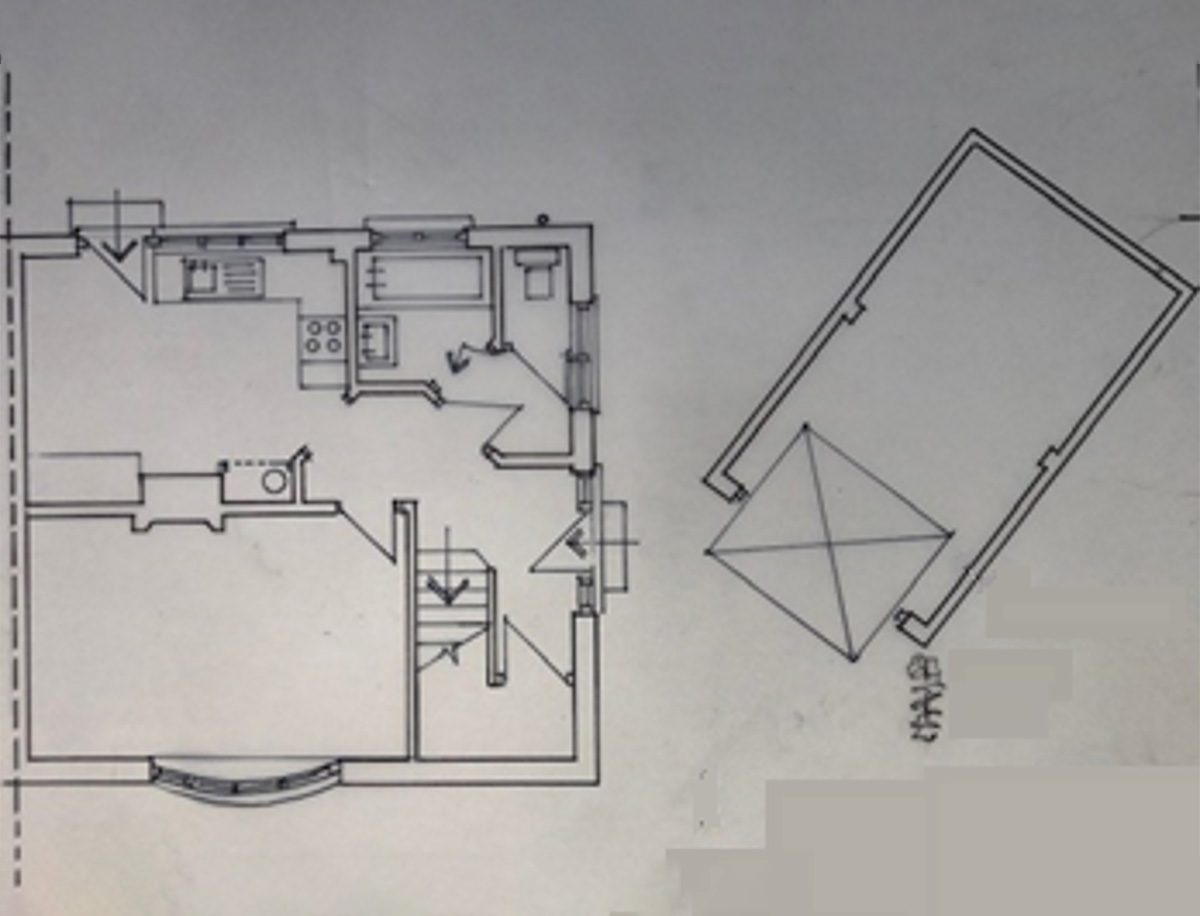

My son and daughter-in-law recently purchased a Type 1 unit, and I was “appointed” architect for its renovation and extension. Because their site was unusually large, we were able to create an extension that almost doubled the ground floor living area. I am intrigued about the effect that this project will have on “world building” at a completely different scale from that of the New Jerusalem Movement in the aftermath of the Second World War — that is, the world building of our three grandchildren as they grow up in their “new” home. As the plans below show, their sensory spatial experiences in these formative years will likely be transformed as a result.

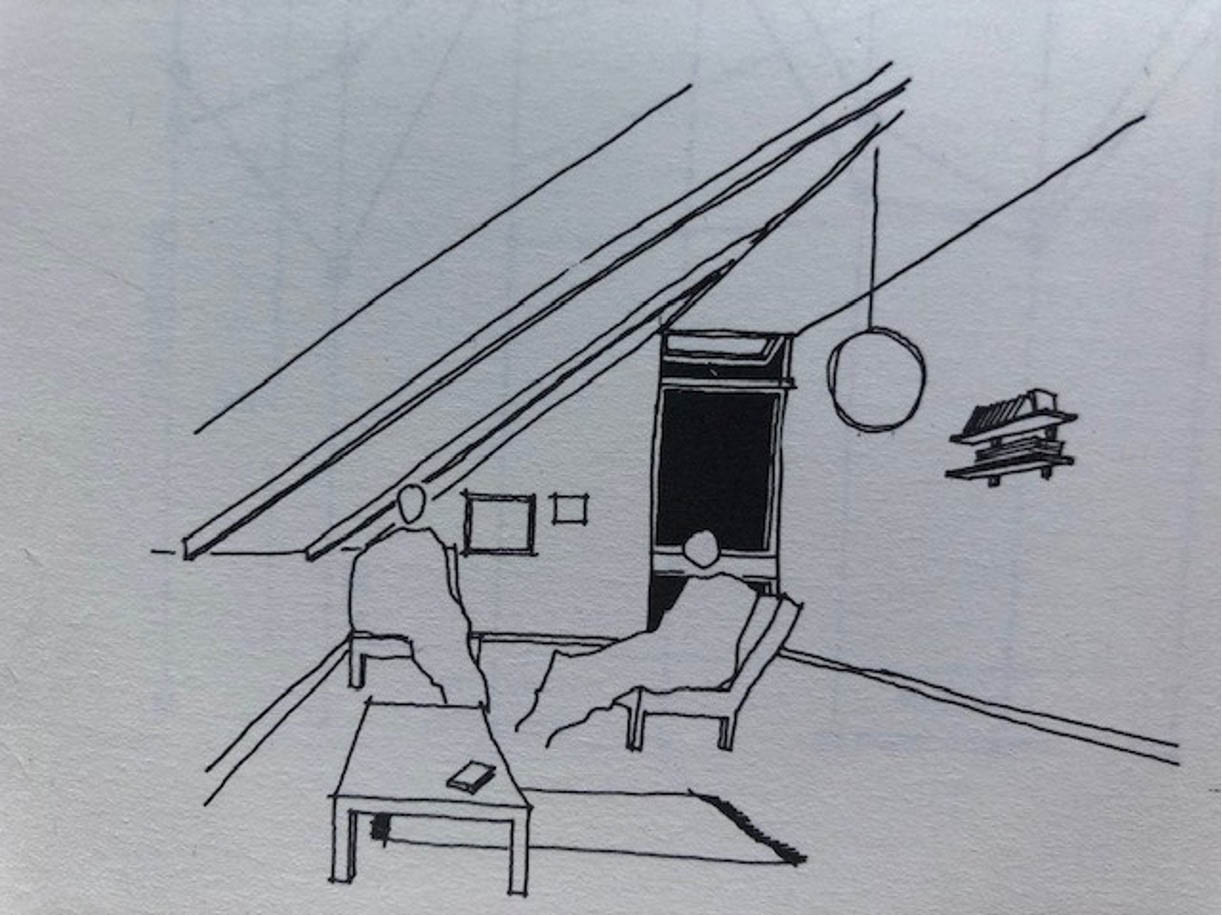

Obvious, in this respect, is the generosity of space and the engagement with the garden. Of more interest to me is the potential impact of the irregular geometry of the newly created living areas. Most of us in the western world grow up in orthogonal spaces, but the accommodation we have created through this expansion is intentionally non-orthogonally arranged. This is also notable within the section of the new living room, which has a mono-pitch roof and sloping ceiling. I am curious to know how this unusual ordering of space will impact our five year, two year and six week old grandchildren as they develop. Beyond curiosity, how can any such impact be recognised, let alone measured?

For example, will their creative play — so important in learning — be influenced by the angular geometries? Will their sensory responses to space and space-making be heightened? Will they be more demanding — or more tolerant - of the unusual in place-making and design?

The Type 1 Cornish Unit, courtesy of Paul Hyett

How space impacts mood, behaviour and performance was my main reason for choosing Canterbury School of Architecture as my initial place of study: the course included a module on architectural psychology. Under that programme, I was fascinated to learn ways in which people are emotionally and psychologically affected by their environments. Not only by the furniture arrangements, but also by the decorations, room sizes and shapes, inter-relationships, décor and colour.

In our own personal ‘world building’, how much have the physical arrangements around us shaped our personalities? As a child, my contextual experience was totally different from that of today’s primary school children. Our Victorian school was a grim, forboding place: high windowsills offered some daylight yet no views out. Our desks were placed in traditionally regimented rows, one behind the other. The teacher’s desk was set on an intimidating raised platform. In contrast, our grandchildren share a large working table with other pupils in a classroom with low windows, all offering views to the playground. A teacher’s table sits quietly amidst the grouping.

Does my experience make me more receptive to hierarchical management structures? Will theirs accelerate development of teamwork skills?

Ground Floor Plan before alteration

Ground Floor Plan after alteration

Placemaking Precedents

Understanding complex spatial arrangements, both within buildings and across cities, has become a science. Scholars such as Kevin Lynch in the USA and Gordon Cullen in the UK have led the way. Their books Image of the City and Concise Landscape explore and seek to explain how we perceive the spaces that make up our public realm. Here in the UK, Alice Coleman’s treatise ‘Utopia on Trial’ has built on Jane Jacobs’ great work ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’.

Regrettably, despite the presence of these classic place-making references, we still understand little of how our personal environments and development influence the way we perceive space, and how we negotiate the public realm outside our front doors. Even trained architects seem largely ill-equipped to understand these psychological and social aspects of world building. That said, through spatial convention and acquired social norms, an acceptable understanding and set of behavioural traits are somehow instilled within us as from a young age to guide us as we make our way in the world.

Traditional classroom set-up (source: Architectural Psychology, RIBA Publications 1970)

For example, if a young man climbs aboard a ‘double-decker’ bus late at night and finds just one lady passenger sitting on the top deck, his choice of seats is influenced by ‘norms’ of behaviour: to sit next to, or immediately behind the woman would be threatening; two seats back would be intimidating. Three ahead or way back and across the aisle would be fine. But these variables are in a constant state of flux: it would be different if the bus was full save for the seat next to her which could then be used; different again if half full; different according to the time of day or night, and so on.

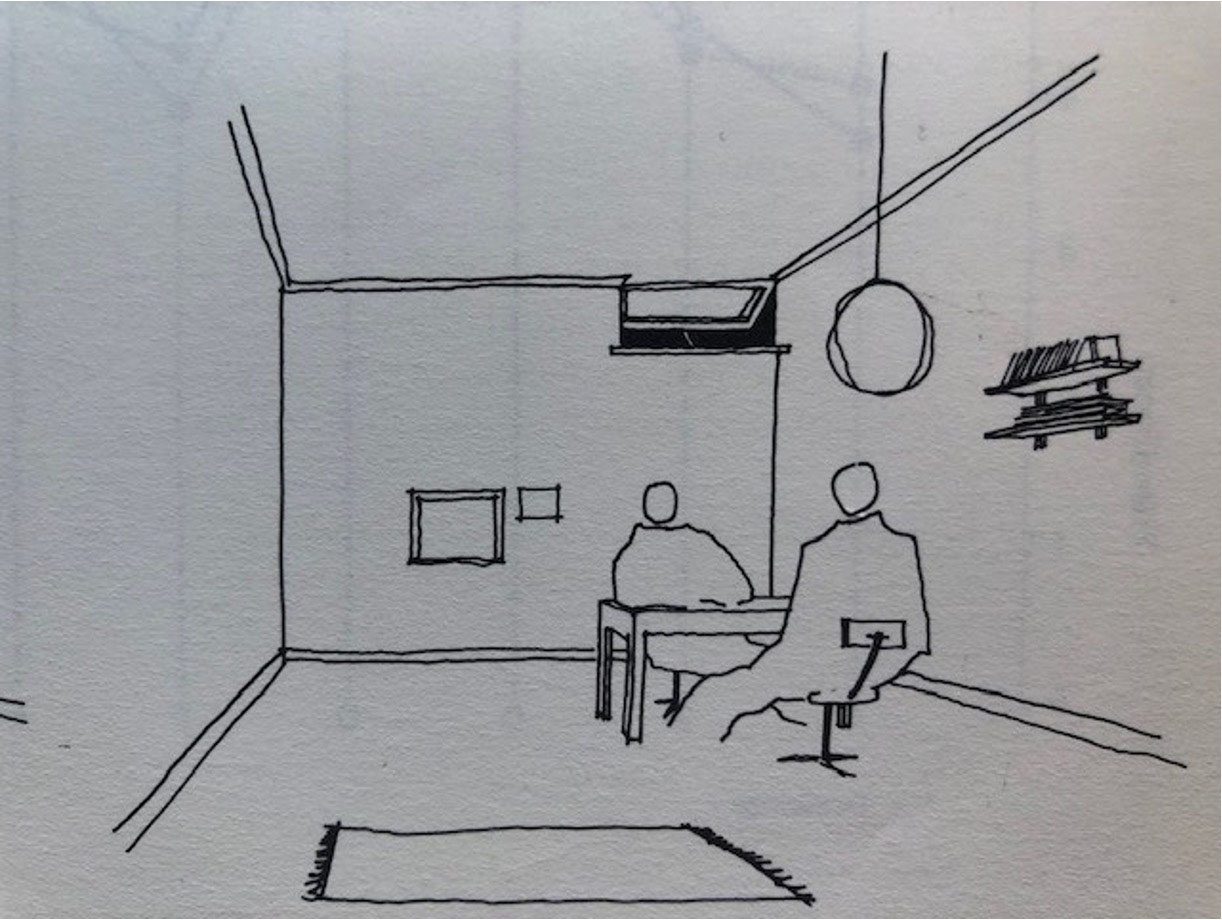

Similarly, the very shape, size and character of a room affects our sense of comfort, as does our position within it. I don’t like sitting with my back to a door in a restaurant; some spaces feel cosy and comfortable, others hostile. The two diagrams below taken from the book Architectural Psychology by David Canter (who taught me back in that first year and who told the double-decker bus story) illustrate the point well:

Most friendly room

Least friendly room

As illustrated, desk and chair groupings formalise or de-formalise the nature of human interaction. Windowless walls, high windows and sloping ceilings likewise all influence a room’s character and may support or detract in encouraging various types of exchange. So, if the living space we have created for our grandchildren to grow up in has a mono-pitched sloping ceiling, good light and free access to a protected and secure garden, how might this influence their development and character against the alternative of an early childhood spent on the 14th floor of an orthogonally planned block of flats with no external balcony or garden?

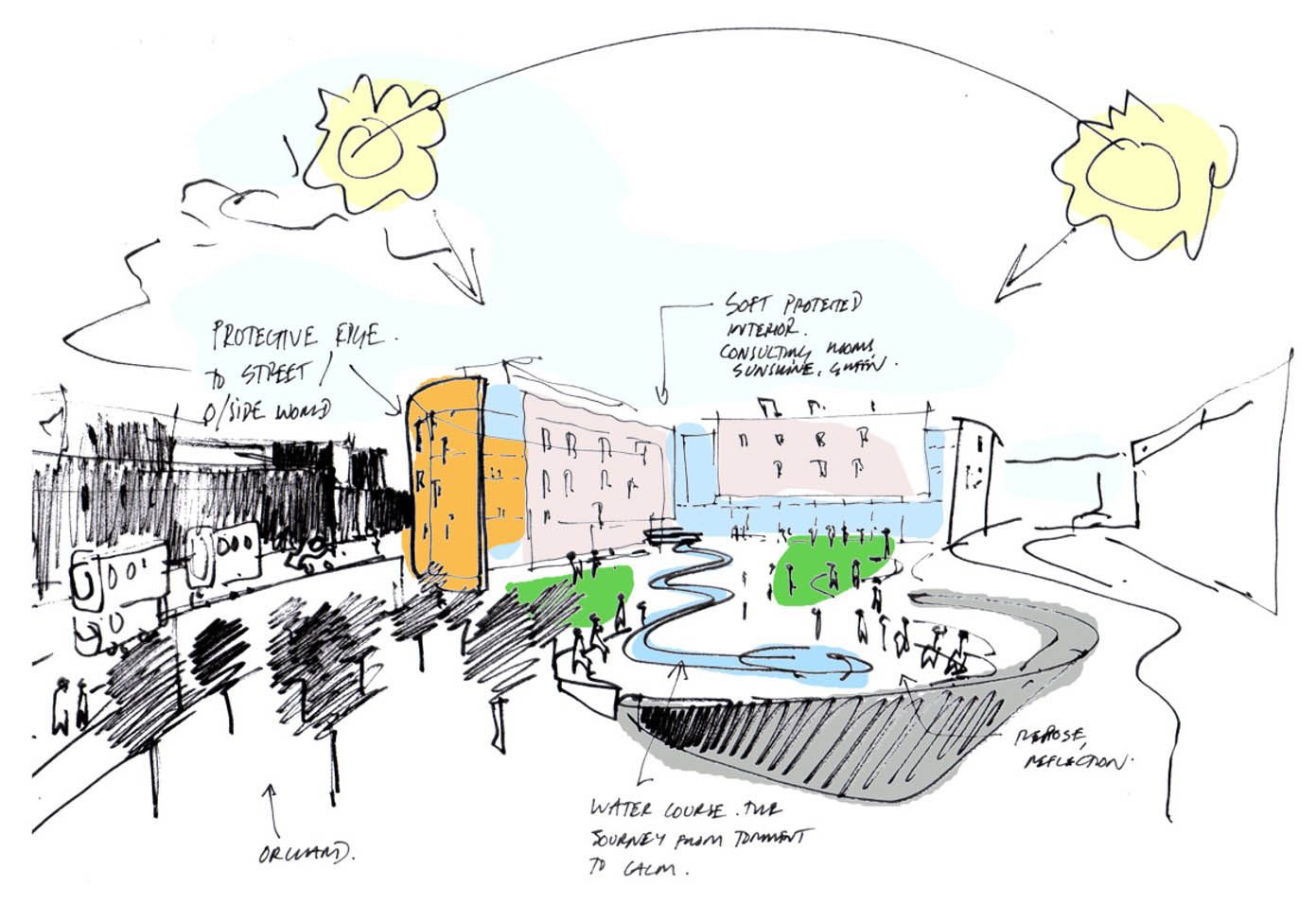

One of my early architectural projects produced severe challenges in this respect, and I drew heavily on those architectural psychology lessons when designing the new Treatment Centre for Torture Victims in north London. At the time of its construction, it was the only building of its kind in the world. To accomplish our design goals, we used curves, light and water features to produce an ambience of calm and security within the busy and noisy city. The curves were in the floor plan, as opposed to in the vertical cross-sectional configuration, because we had been forewarned: Vaulted ceilings in windowless rooms could be reminiscent of the cellars or dungeons in which the patients had been incarcerated, often as hostages under constant threat of death.

Concept Sketch for the Treatment Centre for Victims of Torture

Architects recognise the power of the plan in encouraging social interaction, although it seems we have much more to do to understand how world building, in developing our children’s formative perceptions of the built environment around them, can be positively supported. A point of beginning in this respect would be a better appreciation of how space, light, furniture arrangements, scale and the interrelationship of spaces — one to another and inside to outside — might affect experience and exchange, mood and performance.

Cross-Generational Principles

Winston Churchill famously remarked, “First we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” To be more broadly leveraged and understood, the principles in this insight should be considered across generations:

- Yes, we do indeed shape our buildings (sometimes, sadly, with widely varying degrees of care and thought).

- That shaping significantly affects the world building skills of our children — the world they build around themselves for understanding and interaction.

- That shaping moulds their interpretation of the physical, manmade environment they must navigate daily — the settings for most of their relationships, exchanges and experiences.

And so, at a time when so many new agendas are emerging for architecture, it seems to me we should revisit some of the basic issues of space-making. Buildings provide the context within which we grow. Spaces matter because of the people who use them. We will learn better, perform better and enjoy life with others better within architectures that lift the spirit, stimulate our senses, and enrich our encounters.

As architecture’s wealth of responsibilities continue its shift from simply making beautiful places, spaces and buildings to enabling human development and well-being, we would do well to realize:

World building matters as much as the world’s buildings do.

Paul Hyett is co-founder of Vickery Hyett Architects, past president of RIBA and a regular contributor to DesignIntelligence.