Unlimited Pedagogy

Melanie Fessel (left)

Principal, TerreformX

Mitchell Joachim (right)

Co-Founder, Terreform ONE

August 3, 2022

Urban design in the expanded field

We are experiencing turbulent times. World building in this context calls for “action thinking” — specifically, action-based thinking — of novel strategies to address the global challenges caused by socio-environmental instability. The urban condition is complex and requires solid research, tangible solutions and new ways of approaching solutions to systems-based problems. In the design disciplines, this urgent realm presents distinctive challenges and opportunities to contribute to positive transformation in society. In academia, innovative pedagogies have the power to bring discipline-centered and methodological skills side by side, making the classroom a platform to create new agencies and urban design applications for use in real-life applications. It also poses an intriguing question:

How does urban design education engage with the real world?

Hybridity Required

To answer that question, a hybridity of teaching, research and practice is required to develop a framework that brings design into the urban dominion. Emerging urban projects demand multi-scalar, circular, regenerative, resilient and interdependent orientations, deriving design tendencies in all scales from multiple sources that include science, technology and policy. Siloed perspectives clearly won’t do. A new world building curriculum seeks to engage urban designers with the realities of everyday life in urbanized environments across the globe. The concept of the Anthropocene current geological age, a period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment, captures the unprecedented impact of human activity on our environment. Our current actions have placed us in the middle of what climate experts have called the sixth mass extinction.1 The most recent United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, from August 2021, also provides essential climate lessons and proclaims a “code red for humanity.”2 Since contemporary urbanization is driven predominantly by an economic mentality founded upon fast growth and short-term interests, it has, as a result, concurrently contributed to long-term debt for successive generations in many negative ways.

A Biocentric Approach

Our human impact has been at the foreground of the climate change debate. But a rethinking of Western environmentalism has expanded to consider more than the human aspects of this question.3 This alternate approach considers the relationship between all species sharing this Earth. This biocentric, holistic perspective of the Earth is deeply rooted in Indigenous communities’ viewpoints, ones long aimed at protecting the Earth’s ecosystem and biodiversity, because climate change affects all forms of life on the planet. Society could adjust its reality in significant, effective ways by assuming a biocentric rather than an anthropocentric perspective of people’s actions. Such a broader view can establish and strengthen an interdependent community between all species through the collective imagining of ideas, tools and design strategies.

A cognitive design agenda grounded in biocentric parameters connects all disciplines and schools of thought. It also mediates between environment, climate and species diversity by rethinking and redesigning the Earth. This agenda, as we have imagined it, is shaped by design at the core and is considered on multiple scales. Recent examples of contemporary approaches to size have migrated to multi-scalar methods. Examining urban design education from this broader perspective allows a new design research agenda to be generated. This agenda is further improved through use of the principles of collaboration and — as an important byproduct — allows for an open-ended approach to engaging with real-world problems, a necessary capability in the contexts of adaptation and evolution.

Building New Worlds: Next Generation Urban Design Professionals

Beyond embracing a broader biocentric paradigm, pedagogy, research and practice — the synergistic systems of urban design — are fundamental in addressing the vulnerabilities of the planet’s ever-urbanizing environment. It is time to advocate for the education and development of the next generation of professionals.

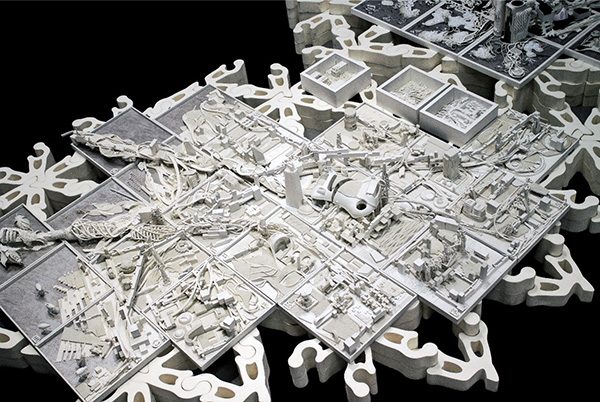

Urbaneering Brooklyn, image courtesy Terreform ONE

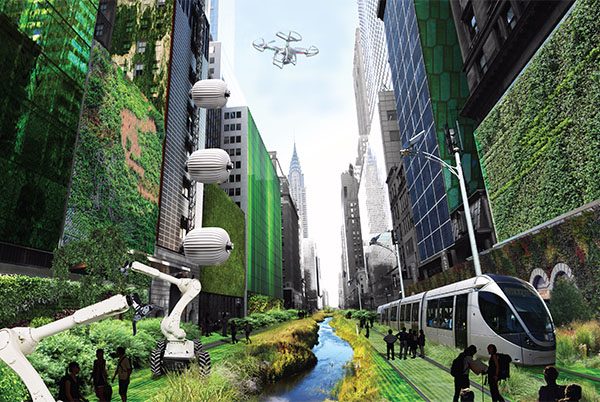

Productive Green 42nd Street NY for Post Carbon City,

image courtesy Terreform ONE

Alternative teaching practices have the potential to ensure that academia engages in critical discourse and expands its vision to connect local and global realities. Based on this belief, we propose to adapt urban design education to build an agency that allows society to invent design tools that fit the 21st century. In this context, the reemergence of the socioecological framework is a catalyst for the urban design pedagogy and the inclusion of interspecies dependencies in design solutions (Abram 1996).4

Concurrent Complimentary Actions?

As educators and practitioners, we have taken a bold and comprehensive point of view to exploring, teaching and deploying an alternative model to urban design solutions. We seek to connect urban design — historically, an often-theoretical discipline — to real-life issues in the real world. Why not? Traditional approaches, paradigms and modalities have contributed to our current reality. We can’t possibly have any more to lose than the current trend is demonstrating. Our final question is this:

What are you doing within your class, your mindsets, your actions, your firms, your clients, consultants and communities to join us in seeking and finding more effective actions and solutions?

Join us.

Melanie Fessel, Dipl.-Ing., M.Arch., Ph.D. candidate

Melanie Fessel is an architect and urban designer. She is a lecturer, academic coordinator and doctoral researcher at the ETH Zurich Department of Architecture. Melanie is principal of TerreformX and director of design at Terreform ONE, nonprofit architecture and urban design research group. Previously, she was head of design development for Alice Aycock Ltd., founding member at ONE LAB and managing editor of Ecogram. Melanie is a former associate fellow with the Cooper Union Institute for Sustainable Design. Her work has been exhibited at White Box Gallery in New York, DOX Center for Contemporary Art in Prague, MASS MoCA in North Adams, the Building Centre in London, DAZ in Berlin, OCAD in Toronto, NAI in Rotterdam and the Venice Biennale. Melanie received her M.Arch. from the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, Dipl.-Ing. from the Technical University of Berlin, Germany, and the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona, Spain.

Mitchell Joachim, Ph.D., Assoc. AIA

Mitchell Joachim is the co-founder of Terreform ONE and associate professor of practice at NYU. Mitchell upholds noteworthy leadership roles

as a university senator and co-chair of Global Design NYU. Formerly, he worked as an architect at the professional of offices of Frank Gehry

in Los Angeles, Moshe Safdie in Massachusetts and I.M. Pei in New York. His design work has been exhibited at MoMA in New York, DOX Center

for Contemporary Art in Prague, MASS MoCA in North Adams, the Building Centre in London, DAZ in Berlin, OCAD in Toronto, NAI in Rotterdam,

Seoul Biennale and Venice Biennale. Previously, he was the Frank Gehry Chair at the University of Toronto and faculty at Pratt, Columbia,

Syracuse, Rensselaer, Washington (St. Louis), Cornell, Parsons and EGS. He earned a Ph.D. at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a

MAUD at Harvard University and a M.Arch. at Columbia University with honors.

1 Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (New York: Henry Holt, 2014).

2 Valérie Masson-Delmotte, Panmao Zhai, et al., eds., Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

3 David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (New York: C. Pantheon Books, 1996).

4 Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous.