Leaving a Legacy

by Bob Berkebile

Founder and Principal Emeritus, BNIM

December 21, 2022

AIA Kemper Award winner Bob Berkebile shares insights on a life of influence and impact.

DesignIntelligence (DI): Congratulations on being this year’s AIA Kemper Award winner, an award given annually for significant service to the AIA. It’s a testimony to the work you’ve done around sustainability and environmental and social issues for decades that has taken root and is setting examples for new generations of followers.

Bob Berkebile (BB): Your congratulations are appreciated, but as you know, this Kemper Award was the result of the inspiring work of many friends and colleagues, such as this year’s gold medalists, Angela Brooks and Larry Scarpa, Ed Mazria before them, my colleagues at BNIM and thousands of other professionals, clients and caring citizens across the planet. I think the award came to me because I am the oldest one still standing.

DI: What was your reaction when you heard the news?

BB: When I received the Kemper medal, after thanking all the folks that had done the work being celebrated, my first comment was a question: “Why are we not all shi**ing our pants?” The reason I have become such a workaholic is that I have continued to follow the climate science since I left Antarctica in ’92. Despite all the good work that has been done to squeeze carbon out of the built environment, the existential threat is far greater today than it was when we started, and we are running out of time!

DI: The sense of urgency is finally hitting home. But putting in perspective might be informative. I find your career story so compelling. Those who have followed the profession since the ‘70s will be familiar with the tragedy at the Kansas City Hyatt, and how you and your firm overcame that unfortunate event in transformative ways. How incredible it is that one small detail could have such impact — on people who lost their lives and on others who changed theirs dramatically for the better as a result, like you.

BB: The Hyatt collapse awakened me to the shocking potential for unintended consequences of our designs, and I was reminded of something Bucky Fuller taught me in college: Failure is a powerful opportunity for transformative discovery. Beyond the 114 lives lost and the 216 who suffered injuries, what were the impacts to families and friends, to the rescue workers and community, to the watershed, airshed and job-shed? How did it change the thinking, knowledge, spirit, wisdom of the community? What could we have done to change those outcomes in positive ways, including the vitality and resilience of the community and its ecosystem?

DI: As further framing, I’d like to go back even further to understand the origins of your journey. What motivated you in school? Were you an aspirant to leadership then? Because of your success in creating a sustained effort to help foster a movement, I’m trying to uncover seeds that may have been planted and grew. Were there external factors? Was it purely intrinsic? Who were your mentors? How can we learn from your experiences?

BB: I was blessed with parents who loved me and taught us (my brother and me) to be observant and to work hard. My mother was a farm girl and one-room schoolteacher. She taught my brother and me to observe nature carefully enough to predict where the best morel mushrooms, blackberries or gooseberries could be harvested the following year. She also taught us to grow food in a one-acre WW2 victory garden.

My father and grandfather taught and groomed me to become the fourth-generation German craftsman contractor in our family. By the time I left for college, I had built a tree house, a woodshop for my dad, a home for my grandmother and one for my parents; in every case, there were critiques and reconstruction.

I was also blessed with mentors in school: an art teacher who helped me claim my creativity in elementary school, a track coach who taught me about preparation and performance, a Spanish teacher who emersed me in language and culture by taking me and a few others to Mexico for a life-changing summer experience. This continued in college with inspiring professors in architecture, fine arts, photojournalism and more. For example, after taking life drawing, sculpture, ceramics, jewelry and silversmithing, the dean of Fine Arts commissioned me to design his home at the edge of campus.

Photojournalism not only taught me to appreciate the importance of light, but also gave me courtside passes and cameras to take award-winning photographs of my classmate, Wilt Chamberlain. Despite all this abundance and good fortune, my most influential professor was Buckminster Fuller, who chose the University of Kansas to explore a new structural type — tensegrity — and our dean chose 15 of us to be with him full time. In a remarkably short period, he changed my worldview and taught me about Spaceship Earth — how to create significant change, to learn from failure, and he helped me refine my “all in” approach to learning by immersion.

I have continued to encounter remarkable mentors who always seem to arrive just as I need them: Amory and Hunter Lovins, Janine Benyus, Paul Hawken, Wes Jackson, Wendell Berry, Leon Shanandoah, Robert Muller and Ray Anderson and more, but they are all either BB (before Bucky) or AB, or BH (before Hyatt) or AH.

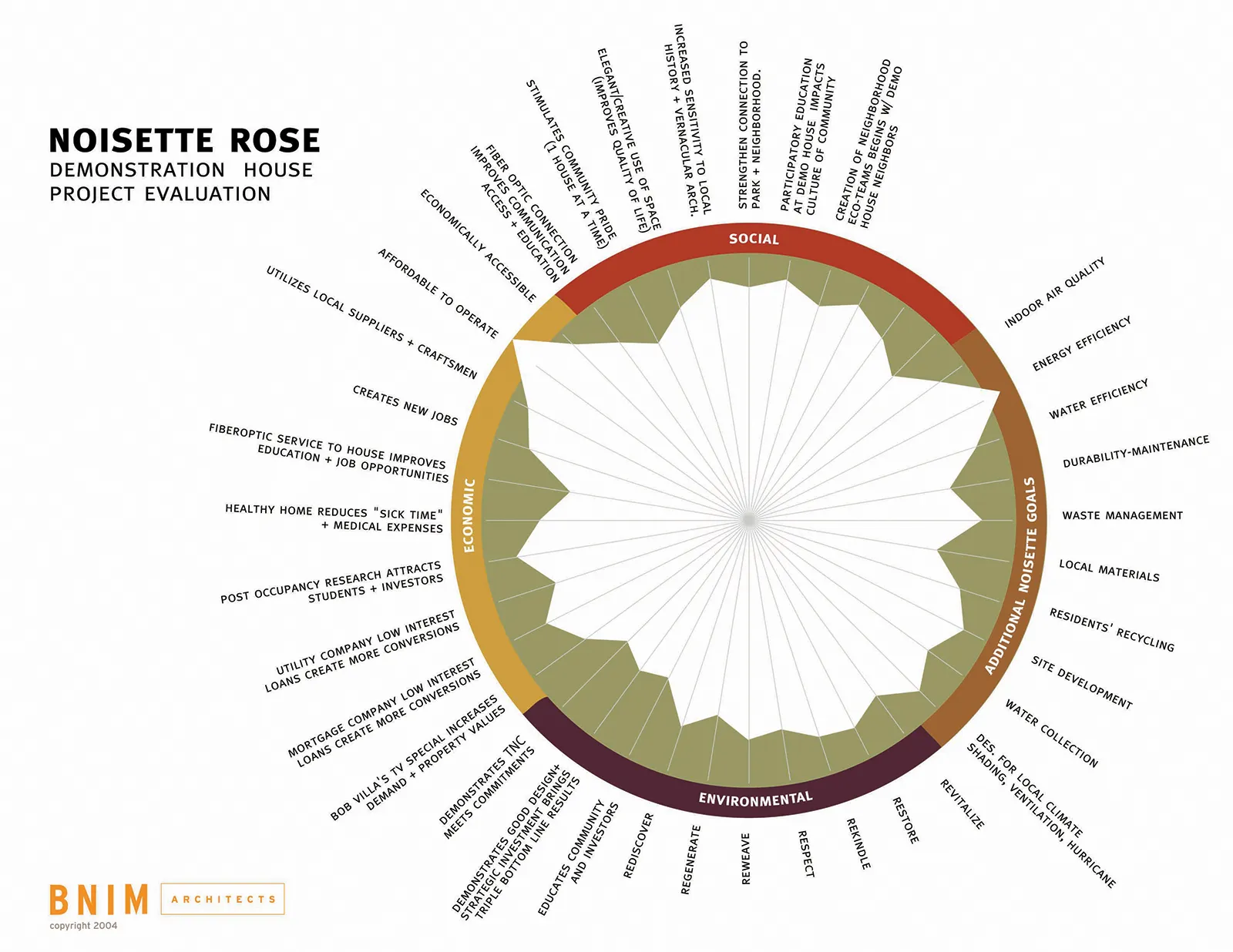

DI: Let’s shift to a tactical, but also a milestone moment. I remember seeing one of your presentations years ago. It was the first time I can remember seeing anything like what you called a “rose diagram,” as I recall. It was scaled plot of dozens of project aspects arrayed radially around a center point. A way for teams to visualize a multitude of factors, not just cost, schedule and the “minimum expectation” benchmarks, but also factors such as community objectives, building performance and environmental goals for water use, energy conservation, etc. All this, years before anyone ever conceived of the acronym LEED.

Your rose was a groundbreaking way to explore a systems approach together among a community of stakeholders. To measure — and visualize — the results of a design effort comprehensively, and, in turn, inform design. Teams having a way to appreciate and keep score of the impact of what they had done was game-changing. Can you share the history of that tool, it’s genesis and current state?

BB: I learned from my mother and Bucky, and later Janine Benyus, that if I was interested in designs that contribute to health, vitality and resilience, it was important to look at the whole system before proposing new ideas. I found, in working with communities, that diagramming the exploration of a systems approach increased participation, understanding and the quality of our collaborative dialogue of discovery together with the quality of the ideas being suggested. It also increases community ownership. We used the Noisette Rose (a flower indigenous to Charleston, South Carolina) as a symbol to explore the appropriate system of values and goals for the community stakeholders in the planning for the redevelopment of the Charleston Naval Base. It’s helpful if the symbol is already part of the community’s culture and if it is flexible enough to adjust the size to display performance over time. We have used other symbols for other projects, but the Noisette Rose was one of the most elegant, and it benefited from strong community participation and ownership.

Noisette Rose, image courtesy BNIM

DI: Has the rose diagram been automated or turned into a dashboard or dynamic reporting tool for the Internet of Things? Many more firms are employing similar tools now, and we need them.

BB: Not by me or our teams, and not that I know of. Arup developed an interesting tool but as I have seen theirs and others’, the critical “dialogue of discovery” is missing.

DI: In hindsight, that was a simple tool to inform how we see, digest and act upon information, yet it had, and still has, much impact. We don’t have enough of those moments in our profession or enough drive to create larger impact. How can we create more similar inflection points?

BB: Other good tools have been created; one of which is a good systems decision tool by Arup, but I don’t know of any that are co-created by the community and design team and are unique to their place, culture and time. We are building on that experience and Paul Hawken’s two most recent books (“Drawdown” and “Regeneration”) to inform the creation of tools for two current projects: the industrial corridor of the Blue River Valley in Kansas City, Missouri (economically similar to the project in North Charleston, South Carolina) and a new hub for regenerative agriculture in the heartland of America, at Powell Gardens (designed by Faye Jones near Kansas City). Both are utilizing a systems approach and have the potential to be transformative. Both will benefit from a strong visual tool that is the result of a collaborative dialogue of discovery.

DI: With all that needs attention, what are you focusing on?

BB: Having just returned from a Rhine River trip from Basel to Amsterdam, I must share what you already know: Europe is suffering from a long-term, major drought, which has lowered the water level in the Rhine River to a 400-year low (similar to our rivers and reservoirs); as a result, the boat we boarded in Basel could not travel to Amsterdam as they normally do, and we were transferred by bus to another boat. In Amsterdam, there was an expo addressing the future of communities and agriculture that was built on land that had been created by dredging. There were some impressive concepts, but I was reminded several times that the Dutch (like us and most of the world) have been fighting nature for years. Ultimately, “nature bats last” (ocean levels are rising while their land continues to subside, and they experience higher levels of salt in their soil). To emphasize this point, together with the latest data released by NASA and CalTech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory about the Thwaites glacier and other thawing/moving ice in Antarctica and elsewhere, which are responding to the increased carbon we have released since I was there, are now poised to raise global sea levels by more than two feet.

I found it depressing, even in Holland, that this is still the mindset: doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. As Einstein pointed out, that’s insane. It motivates me to be more creative, collaborative and to work with nature on our current projects in the industrial corridor of the Blue River Valley in Kansas City and the Regenerative Ag Hub at Powell Gardens. In both cases, the community intends to use regenerative strategies to teach people to grow healthier food while building soil, capturing water and sequestering carbon, and rebuilding a healthy, vital, resilient community through a JEDI (just, equitable, diverse, inclusive) lens.

Westport Commons

Image courtesy Ryan McCabe, BNIM

DI: You also mentioned you are currently working with two groups in efforts with the potential for significant impact. Can you share any details?

BB: The Foundation for Regeneration has just completed the listening/discovery phase and is now working with Metabolic and others to gather the data to inform the next critical moves while seeking funding to launch the first pilot projects to revitalize and transform the Blue River Corridor (a severely damaged industrial corridor with several fragile neighborhoods). We’re taking the advice Bucky Fuller offered repeatedly: “The only way to make significant change is to make the thing you are trying to change obsolete.” Our pilot projects are designed to prove that the old systems are obsolete and make the case for systems thinking, a circular economy (waste to value), regenerative land management and agriculture, over the obsolete industrial take, make, waste management systems that ravaged this once beautiful asset within our city.

The second group, Heartland P5 Partners (P5 means perpetual prosperity for people, place and planet) and Good Oak are completing the planning and fundraising and will soon begin the infrastructure to launch a regenerative agricultural hub with the Audubon Society, Lincoln University, Evergreen Ranching and the USDA at Powell Gardens—designed by Faye Jones.

DI: What did it take to form breakthrough collaborations like these?

BB: These partnerships arrived in similar ways to the mentors I have enjoyed over the years: They seemed to find us as we observed critical issues in the community and shared what the challenges and possibilities could include. As the problem and needs became clear, the stakeholders and potential partners also appeared, or at least became more obvious.

DI: In such sweeping partnerships, surely there are different motivating factors for each entity. Can you talk about the economics and incentives? So often, efforts don’t start or are derailed due to the “rules of the game” being established in unsupportive ways, e.g., first cost and short-term mindsets.

BB: Of course, there are many diverse motivations among the stakeholders on projects, which is why the systems-based collaborative dialogue of discovery is critical. As Meg Wheatley pointed out so eloquently, “There is no force more powerful than a community that has discovered what it truly cares about.” Once that discovery has been made, it’s much easier to create priorities, designs and strategies that address the needs of the entire community and underlying ecosystems on short- and long-term bases.

DI: I have to believe the process turns quickly to politics and negotiation. Assuming you had an architectural education close to mine, we didn’t learn those skills in school. We learned to draw, design and detail. Have you acquired a taste for these new skills, or do you pass the baton to experts for such things?

BB: I think we had a similar education, but I encountered Bucky, who pointed out that every decision I/we make either has a positive or negative impact on Spaceship Earth, no exceptions! This realization forever changed my viewpoint and led me to acquire new skills not available in the architectural programs.

DI: In your role as principal emeritus and your career arc, you are in position to champion “greater good” kinds of causes. I can draw parallels to the post-presidency work still ongoing by former Presidents Carter, Clinton and Obama on world health, water resources and environmental issues. Huge, wicked, systemic problems, ones only leaders with such respect and credibility seem fit to champion. I can see similarities in your pursuits and results. As you reflect, how can we engender more of such leadership, and not just by those in the late phases of their careers?

BB: Ironically, I have worked with all three of those presidents plus both Bushes (some more than others and some with more joy than others) plus Gorbachev (on a project for Habitat International, with Carter). I found them all to be very different, but effective to different degrees for different reasons. I’m convinced Carter has been our most impressive past president for impact and am hopeful that Obama will move in that direction, and the design of his library in Chicago seems to forecast that possibility. As to your question, we desperately need young voices and minds engaged in redefining the future of humankind and the planet. Brian Weinberg, my co-founder of the Foundation for Regeneration (working in the Blue River Valley) is 36, and most of my partners in Heartland P5 and Regen Partners working on the Regen Ag Hub and food systems are between 30 and 50. We find that my age, experience and reputation might open some political or corporate doors but, once open, my younger partners will often lead the conversation/exploration. Their energy and knowledge are impressive, as is their command of new technologies and social media.

DI: What do architects and design professionals need to do to exert more influence and have greater impact? The weeping and gnashing of teeth continues, either about our diminishing roles as professionals or the state of the environment, but there’s not enough action. For the most part, we’re not willing to change our behavior. How must we change to improve our lot and that of those we serve?

BB: The world is changing dramatically, and we are surrounded by overwhelming evidence that we are facing the existential threat of climate change — a direct result of our obsolete thinking and designs. Without a dramatic shift in our designs and community systems, our children and grandchildren face an uncertain future. If you believe the moment of greatest danger is the moment of greatest opportunity, as I do, our profession and the human family have never seen such an opportunity! Our children’s and grandchildren’s lives depend on our response! In my mind, there is no time for whining about diminishing leadership roles; the only option is to understand the problem and develop regenerative design solutions that reuse empty or underutilized structures, neighborhoods and infrastructure while sequestering carbon aggressively — in short, creating next-generation living buildings. The leadership awards will go to the architects whose grandchildren are proud of their efforts to design a better future.

DI: Knowing all you have going on, you are kind to talk with us. Thank you for your commitment, inspiring work and all that you do. Any final thoughts? Do you see yourself ever slowing down?

BB: Thank you for speaking with me and inviting your readers to join us in creating new regenerative design solutions to work with nature to reverse climate change, or at least slow it down enough to buy time for the next generation to reverse the damage we have done and create the time for nature to restore Spaceship Earth before the human family becomes extinct.

At 45, I imagined I would be kicking back at 65 and enjoying family, painting and traveling, but at 85, knowing what I know, I can’t slow down and look my grandkids in the face. What a privilege to do all I can every day to create a future for my family.

DI: Thank you for the wonderful legacy you are continuing to leave, sir.

Bob Berkebile, FAIA is founder and principal emeritus with BNIM, a leading light in championing sustainability in design, construction and operation of the built environment, and the recent winner of the American Architects’ Kemper Award.

Any list of accomplished, influential environmentalists and preservationists includes Bob Berkebile. Highly regarded by fellow professionals, Bob focuses on improving the quality of life in our society with the integrity and spirit of his firm’s work. In 2009, Bob received a Heinz Award from Theresa Heinz and the Heinz Family Foundation for his role in promoting green building design and for his commitment and action toward restoring social, economic and environmental vitality to America’s communities through sustainable architecture and planning. Among his contributions to his industry, Bob is the founding chairman of the American Institute of Architects’ National Committee on the Environment (AIA / COTE) was instrumental in the formation of the U.S. Green Building Council and its LEED rating system and has worked with five U.S. presidents on environmental policy reform.

Since retiring from BNIM, Bob has formed a development company that focuses on urban acupuncture — an intervention on a dormant community asset to create a catalyst for community vitality and resilience. His company’s efforts have yielded the transformation of Kansas City’s shuttered Westport Schools into Plexpod Westport Commons, an award-winning co-working facility, community forum, and housing; and the conversion of Commerce Tower (a 30-story former bank headquarters/office building) into a vertical neighborhood of schools, services, and 330 apartments. His company’s current work includes the redevelopment of the Blue River watershed and surrounding neighborhoods to transform a collection of abandoned industrial, military, and other sites into a regenerative economy for the community, and a regenerative agriculture hub at Powell Botanical Gardens.