Striking a Balance

by Jennifer Stone

Partner, Robert A.M. Stern Architects

February 15, 2023

RAMSA’s Jennifer Stone discusses resilient design and historical context.

DesignIntelligence (DI): We are talking with Jennifer Stone, partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA), a leading global architectural firm based in New York City. Your firm’s work is well known for its classical, historical references. Your website talks about your dedication to preserve a “sense of place.” In line with our editorial theme for this quarter — resilient security — how does your firm’s work relate to that idea?

Jennifer Stone (JS): We have a commitment to planning and designing buildings that create spaces for communities that are sustainable, accessible and safe. As architects, we have a responsibility to create designs that protect and honor our historic buildings and encourage adaptive reuse to positively affect the environment. RAMSA’s work often relates to resiliency and security — we create buildings and places that achieve a sense of permanence through their quality of design, material choices, the climate in which they reside and how they relate to the public realm.

Within the industry, there is a larger understanding of the built environment and its contributions to the climate crisis. For many of the projects I work on, we specify materials and use systems that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and move us toward carbon neutrality. This is a positive and important shift, as it recognizes our profession’s role in developing greener practices and creating a more sustainable world. Many of the projects I’ve been a part of at RAMSA have achieved LEED Platinum and Gold certifications. Often — as one of my colleagues, Preston Gumberich, recently said about the firm’s work on Colgate’s campus — there’s a popular perception that sustainability is somehow at odds with classically inspired design. In fact, elements like fewer glazed openings and thick masonry walls are inherently conducive to energy efficiency.

DI: Your educational background at Notre Dame with its classical pedagogical bent would seem to serve you well working at RAMSA. Was doing classically derived work a personal focus? Did it steer your pursuit of a career working with Robert Stern and the partners at RAMSA?

JS: I remember the day I was convinced to join the School of Architecture at Notre Dame as a high school student. It was during a campus visit on a beautiful fall football weekend. I was visiting my brother, who was graduating, and I stayed with his girlfriend. Her roommate was my current partner, Melissa DelVecchio. Missy was also graduating from the architecture school. She toured me around and told me everything about the program — including a year in Rome! I was sold. Who knew Missy and I would eventually become partners practicing together in New York City after so many years?

A Notre Dame education is an excellent foundation and training ground to understand basic design principles like scale and proportion, which transcend architectural style. Being there taught me how to solve problems through research by studying precedent, context and examples of what works and what doesn’t. No matter which architectural style you work in, understanding precedent and context are essential. These skills equip you to solve project-specific challenges and intelligently address the questions at hand. The faculty prepared us — and still prepares students — to apply time-tested principles and critical thinking to a myriad of issues and situations within the realm of design and beyond.

My clients and projects at RAMSA have allowed me to apply these lessons to a wide variety of building types, contexts and architectural characters. At RAMSA, we are careful to consider our clients’ needs and their site’s unique situation, regardless of scale, style or context.

DI: Sticking with your personal background, you’ve had significant involvement in the women in architecture organizations and on the board of Beverly Willis’ BEVY Foundation. Congratulations on that. I interviewed Beverly for my book “Managing Design.” She is so wonderful and does so much to give back after seven decades. Did you have strong women mentors?

JS: Yes, and I’ve also had the recent pleasure of co-chairing their 20th anniversary and annual gala this past October. Beverly is a pioneer and role model for so many of us in the industry.

Since the beginning of my career, I’ve been fortunate to have a strong support system of women surrounding me. I’ve never been too shy to call on them and seek their advice. Their support has helped me get to where I am today.

Since I joined RAMSA in 2000, I’ve seen lot of change in our industry and within our firm. Today, I’m involved with our firm’s Women’s Leadership Initiative (WLI). Our mission is to develop and promote women’s growth in the profession through education, mentorship and peer support. Helping my colleagues meet their professional development goals has been truly gratifying and it feels as though my career has come full circle in some ways.

Importantly, the structure of WLI has been a model to other employee resource groups at RAMSA, such as RAMSA Q+, which promotes the inclusion and acceptance of LGBTQ+ individuals in architecture, and RAMSA IDEA, which is the firm’s inclusion, diversity and equity alliance. I believe our combined programming has created a more sensitive and inclusive work environment.

In addition to the Beverly Willis Foundation, I have found a wonderful network of women in leadership positions in our industry through my membership and involvement on boards with the New York Building Congress, the Society of College and University Planning, the Urban Land Institute and the Women’s Forum of New York.

These organizations have been an invaluable resource, places where I have built a reliable community and a resilient support system of colleagues and friends. We still have a lot of work to do, but, as a collective, we have the momentum to create change.

DI: Back to your work. Our resilient security theme invokes architectural ideologies such as those of Robert Venturi and his decorated sheds, and the modernist work of Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano in creating long-span loft spaces flexible for evolving programs and uses over the years. The prevailing brand of your firm’s work and its wonderful use of lasting materials, such as brick, stone and traditional forms, always achieve the sense of permanent history desired in the building types you do: residential, academic and cultural. But in a rapidly changing world, how does a desire for adaptability and flexibility reconcile itself with your portfolio — a body of work that often looks historical?

JS: When we are approached with a specific site, we are always determining the most appropriate choice based on our client’s needs, the neighborhood context and surrounding buildings. Creating buildings inspired by tradition is not a hard rule across the firm. Many buildings in our portfolio do not appear historical. Our designs fit the character and architectural language of the neighborhood or city we’re working in. A building clad in limestone in New York City wouldn’t fit in a city like Miami, with predominantly glass buildings. But we’ve done both very successfully.

As a rule, our buildings use a wide variety of durable, sustainable materials. We consistently push our clients to think far into the future. Many buildings get torn down because they’re badly built or badly designed — they can’t accommodate changing needs or functions, or because their appearance is no longer in vogue. We’re trying to avoid that.

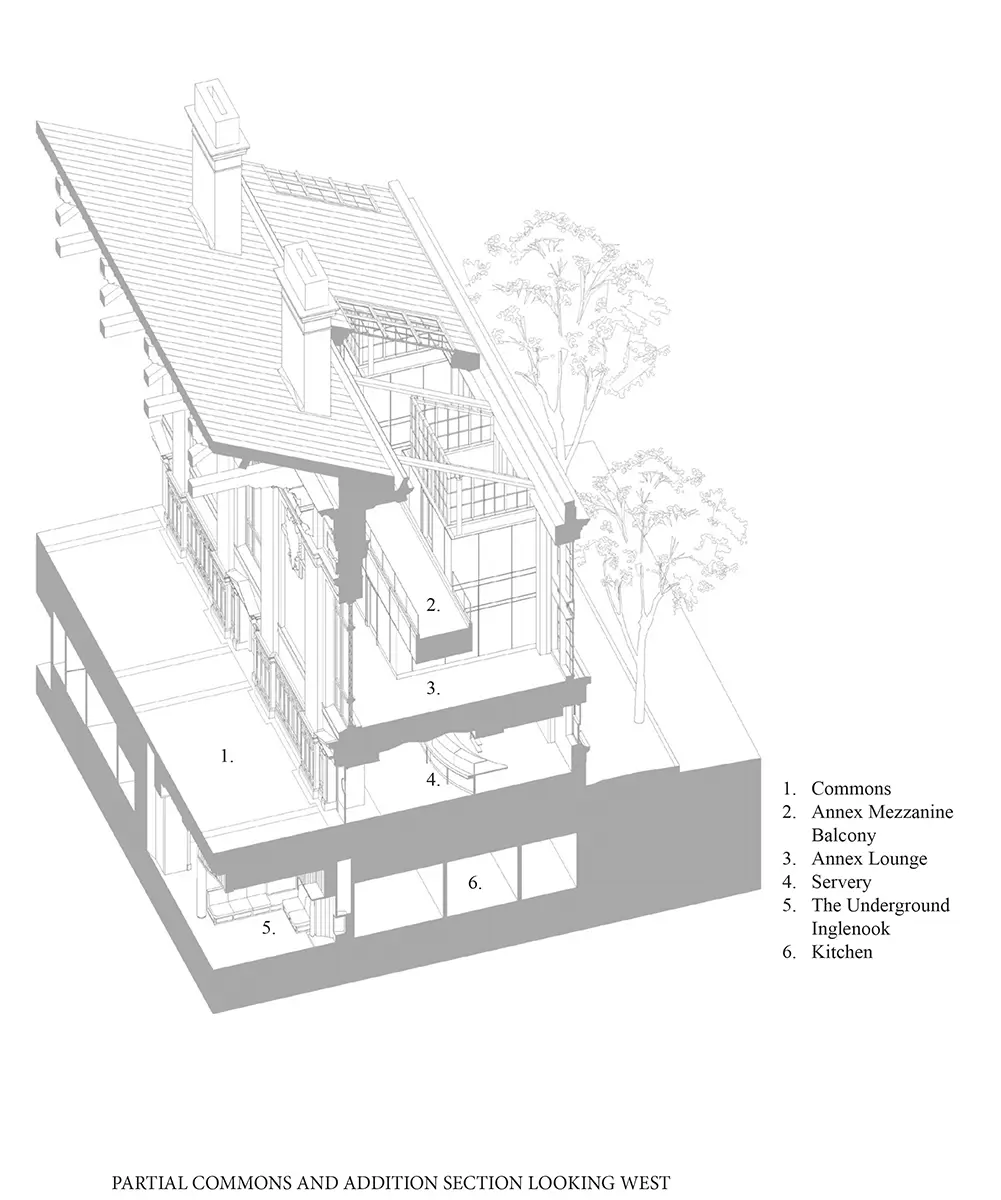

For example, earlier this year, we broke ground on a renovation and expansion of the University of Virginia’s McIntire School of Commerce. The project entailed modernizing Cobb Hall, a classical brick building built in 1917 that had become outdated and no longer met the university’s needs. Instead of creating something brand new, our design creates collaborative, flexible spaces designed to meet the needs of the university today while still fitting into its historic context. We’ve achieved something similar with the recently completed Schwarzman Center on Yale’s campus, which offers students an adaptable, modern student center that also preserves the historical campus buildings.

In both cases, understanding and respecting the university’s historic contexts has allowed us to play within those parameters, creating adaptable, flexible spaces that meet modern needs in a contextually appropriate manner. That’s a balancing act we’re particularly adept at striking.

Ultimately, we lean on the elements we feel are important for maintaining a sense of continuity and coherence with a building’s context, but we’re not afraid to adapt tradition to fulfill our client’s needs. We’re not trying to create buildings of a specific time as much as we are trying to create buildings that span time.

DI: Let’s shift to process. You describe yourself as a research-driven firm. How does that integrate itself into your design process?

JS: Research and academia are uniquely at the core of RAMSA’s culture and approach. Our client’s goals, their program and space needs, the site and its context are all variables that change on a project-to-project basis. The only way to effectively address all these different elements is through research. That includes research into precedent and context, but also in the form of truly understanding our clients and their needs. In fact, RAMSA has one of the largest private libraries in the country. We also have a research team, with staff who have scholarly backgrounds in architecture and who are uniquely responsible for supporting design teams with historical and precedent research. But more than just reviewing preexisting literature, we also spend time at the site to understand the local customs, climate and how people live and work.

With our buildings, we like to say that we paint portraits of our clients. Doing this successfully requires researching our clients, their programmatic needs and the context and environment they exist within. When it comes to resilience and innovating new practices, we’re constantly engaging our in-house experts and consultants who are leading in sustainable design. We’re always thinking early in our process about how we can optimize our designs for health, wellness, restoration and resilience.

With this research and knowledge at our fingertips, our design process is collaborative and iterative. We explore many options — often while building consensus — before developing one solution.

DI: How can we increase expertise and add certainty for our clients? I’m thinking about things like design-assist, specialists, and involving consultants, contractors, trade contractors and manufacturers to inform performance, cost estimating, constructability and scheduling? Having spent 30 years as a traditional, design-focused, architect myself, and then another 20 as a design management liaison inside a national construction management firm, I embrace the idea of broadened collaboration and involvement. What’s your stance? I have a perception, perhaps woefully inaccurate, that much of your work is still design/bid/build and that contractors are seen as evil necessities. Am I wrong?

JS: Absolutely! Seriously … RAMSA has done several design/build and Public Private Partnership projects, which involve a unified team approach from start to finish. It’s accurate that a majority of our work is design/bid/build, but we enjoy productive collaborative relationships with many builders. The high quality of our collective work is evidence of that.

I call the most important phase of the project “Phase Zero,” which is the setting up of a project. Establishing strong communication, getting to know your client, and setting expectations are the most important part of any planning or building project, for schedules and budgets especially.

A crucial piece of that process is confirming who is involved and when decisions need to be made. While one size does not fit all, my experience working on large and complex projects is that integrated design and having everyone at the table early on, including the contractors building your design, is critical to a project’s success.

DI: So true about “Phase Zero.” Let’s go a bit more open-ended. The world has been hit by pandemics, recessions, political strife in the prevalence of mis- and disinformation. Within the firm, who is looking to the future? What is the future telling you and how are you responding to adapt, evolve and anticipate it? How might it transform your design process?

JS: As architects, we’re always looking to the future in one way or another. That’s inherent in what we do. I have the good fortune of collaborating with 16 other partners at RAMSA as we tackle these issues head-on. More broadly, we have a team of nearly 300 brilliant individuals at the firm we collaborate with to push the envelope to create more beautiful, healthier, more resilient environments.

As an industry, the future is telling us to build more sustainably. That’s tied to our firm’s focus on longevity and adaptive reuse, but also to our belief in the importance of introducing appropriate density into urban centers. Then there’s the growing consensus that architecture and development are demanding more diverse perspectives and voices. Internally, WLI, RAMSA IDEA and RAMSA Q+ are advancing that conversation around equity and inclusion. To be more effective, it’s important to work with other colleagues within the industry to push for change.

Recent years have magnified the importance of health and well-being for design firms everywhere. Internally, we’re continuing to navigate how we can work in ways that are creatively fruitful and maintain a sense of community, while allowing for flexibility.

A few months ago, my colleague Sarge Gardiner observed how Zoom calls seem to dissolve hierarchy. On screen, every face is the same size regardless of seniority. Sarge noticed how that has been conducive to getting ideas from all corners of the firm. That’s stuck with me. As we always try to do as architects, we’re observing what’s going on around us and trying to respond in meaningful ways.

I feel fortunate to have RAMSA’s long-standing reputation for design excellence as a foundation. I feel even more fortunate and optimistic about my smart, talented, passionate colleagues who continue to enthusiastically solve any challenge that comes our way. Our field is ever-changing and advancing. It has incredible power to positively influence the way people live. Yes, we’re facing a convergence of crises, but as stewards of the built environment, we will adapt — just as we always have. We have an incredible opportunity ahead to achieve impactful solutions.

Jennifer Stone, AIA, is a partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects. Experienced in managing complex institutional planning and design projects, Jennifer brings a love of contextually appropriate, sustainable architecture to her work with clients, communities and building industry partners. Balancing a passion for creating places that stand the test of time with proven ability to build consensus and get things done, she has overseen major planning and capital projects for institutional clients across the country. Her work addresses specific client needs while applying socially responsible and sustainable design strategies that benefit the broader community. An advocate for high-quality design and collaborative problem-solving, her talent for bringing together the diverse voices of academic, administrative and community stakeholders helps envision and build a shared future.

As partner, Jennifer has helped realize ambitious academic and cultural projects such as the Yale Residential College, the Harvard Law School Campus Master Plan, the LEED Platinum-certified George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University and the Mark Twain House Museum Center, the first LEED-certified museum in the U.S. Current projects include work at the University of Virginia and the University of Georgia.

Jennifer is an active participant, mentor and volunteer in her professional community. As a council member of the Society for College and University Planning, she shares her extensive knowledge and global best practices. Her presentations at numerous professional conferences and her leadership roles with the New York Building Foundation, the Beverly Willis Architectural Foundation, ACE Mentorship Programs and the Urban Land Institute, as well as the firm’s Women Leadership Initiative and Sustainability Committee, testify to her commitment to developing and opening the field of architecture.