Advocacy: The Impact of Architects

by Dick Thomas

The need for great architecture has never been more urgent, the challenge to creating it never more complex. At SHP we believe our mission is informed by three things: design, research and advocacy. For most of us, the value of design is where we were born. Research underpins the way we solve problems. Advocacy is the new kid on the block. Like good design, advocacy requires a commitment to a belief and mission that adds deeper value to the solutions we provide, not just to our clients but to a larger context, one that embraces empathy around differing points of view that learn from the past and embrace constant change and improvement.

A number of things shaped this article. The first was a workshop sponsored by Autodesk in 2015 under the moniker of “IDEAS: The Innovation + Design Series.” The specific session centered on the following question: How can we foster a design mindset in education to help more people to cultivate 21st century skills? Out of this experience, I asked myself if I had been designing educational facilities to an outdated and inadequate paradigm. It caused me to completely re-think how I apply the skills I’ve learned as an architect to the challenges, large and small, of the world today.

The second was a Futurecasting event that SHP executed that informed the future mission and vision of the firm, as well as underpinned the co-authoring of a book called “9 Billion Schools: Why the World Needs Lifelong Personalized Learning for All.”

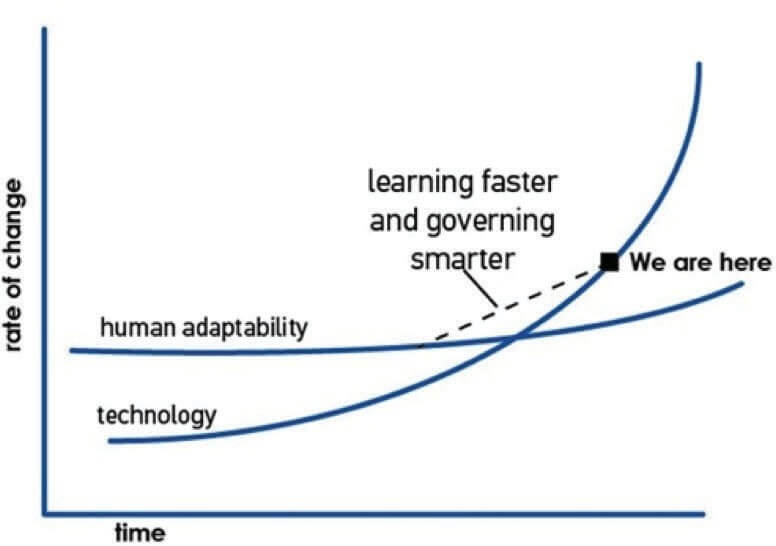

Another was reading Tom Friedman’s book titled “Thank You for Being Late,”1 in which he discusses the “AstroTeller Curve”— a unique perspective on the pace of change in our world today (see below).

Source: “Thank You for Being Late” by Tom Friedman

Just as the maturation of the value of the “I” (Information) in Building Information Modeling (BIM) is rapidly changing how we document the buildings we design by adding value up front in the form of data, so too must we integrate higher value into the decisions that go into “what” we design. We need to advocate for deeper, more meaningful solutions to the “wicked” challenges we face. Repeating past mistakes of paradigm serves no one in the long-run. Becoming part of the hard work of changing mindsets and informing the future versus reacting to it is difficult and doesn’t happen by flipping a switch. It requires a decision to devote time, resources and energy to learning constantly about the issues, researching possibilities, and broadening our reach and influence. It requires a kind of advocacy for both the higher level mission (lifelong learning) we serve and our role in advancing it.

Architects have great power to impact the multitude of issues facing our society and culture today. By leveraging our innate skills in applying design thinking and design skills to the problems in our world, we can lead in building a better world. In the simplest of terms, our focus needs to expand from simply responding to a program defined by others, to helping define the program to which others must adapt. In short, we must advocate for change to the basic ways we have been conditioned to respond by taking on problems at the source of the question, rather than the arguably predetermined answer as reflected by the POR (Program of Requirements). This is an enormous, scary and perhaps risky challenge, to which I believe we are called … or should be.

SHP has responded to the call for advocacy over the past twenty-five years in several ways.

One way is in recognizing that architecture, as Dana Cuff would argue, is a “social construct.” In the early 1980s, SHP adopted a process centered on the power of the voice of the customer and it was called the “Schoolhouse of Quality.” The process advocated for and interjected the voice of all those influenced and/or affected by the buildings we designed directly into the design process. It was influenced by and derived from the work of W. Edwards Demming and the application of TQM (Total Quality Management) methodologies into the auto industry. Our advocating for better ideas by all those closest to the issues was celebrated. It was a critical success factor in moving SHP from a local design voice to a regional power house — setting the firm up to elevate its design work and status in the conversation about education.

John Tocci, of Tocci Construction and co-founder of the BIM Forum, is famous for introducing many BIM Forum events with statistics that indicate our trillion-dollar industry regularly operates on a 30% to 50% inefficiency ratio, wasting between $300 billion and $500 billion a year! The numbers are staggering and embarrassing even at the lowest percentages. How this happens belongs to everyone that participates in the business, and I include myself in that. To combat the issue and to advocate for the efficacy of a better way, SHP led an effort to redefine the process of design and construction some 10 years prior to the first conversation about Integrated Project Delivery (IPD).

In 2000, SHP and a leading major construction company joined forces to implement the concept of Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) as a means to deliver better-designed, higher-quality facilities with lower risk for all involved. SHP and the construction company shared total project value risk equally (to the penny!) across the board, and developed performance compensation incentives and processes that were highly collaborative from start to finish. We blew apart standard delivery methodologies, employing state-of-the-art pull planning and last-planner strategies when such process models were in their infancy. We pushed the early adoption of Revit technologies and the application of the power of BIM and led the firm’s transition to the potential ability to leverage the data we were producing well into the future.

Advocacy can take many forms and it would be undeniably wrong for me to suggest that the profession has been devoid of the concept of advocacy. We advocate for “DESIGN” and its power to make lives better. Good design is a powerful positive influence anywhere it is applied. I would be equally wrong to suggest that the profession has failed to make lives better through design. It has done so in spades, and I am proud to be an architect and a member of such a noble endeavor. I am not arguing the we as a profession have failed per se, but that we are selling ourselves short and can do (must do?) more if we are to continue to even hope we’ll be in any position to control our own destiny. I am not alone in that belief and am inspired by others that have come to the same conclusions and have developed ways to spread the message and include others in leveraging our skills toward a better future.

Several examples come to mind. The first is HMC Architects, who in 2008, formed a non-profit called the Designing Futures Foundation. Their mission is to give back to the communities the firm serves. Another example is InScapePublico, a non-profit architecture firm whose mission is to provide affordable professional architecture services to other nonprofits and the people they serve. A third example is the Open Hand Studio of Cannon Design that works as an incubator for public-interest design projects within the firm with a two-pronged approach to giving back.

Each of these examples speak to outreach and either support them through access to funds, or reduced cost via pro-bono services or reduced fees that create a more fertile environment for problem-solving in a related context to the value of design. They are to be applauded for their work. There are numerous other firms and organization that take on advocacy in ways that support their role in the community and their positions on particular social issues.

The way we, as professionals, were taught to solve problems has enormous value in addressing the challenges of the future. When in school we were taught that the first step in design was to understand as much as possible, what was there to know about “who was asking?” Today’s favorite descriptor is the term “empathy” — to ask not just “what was the program?” but to explore much more deeply what the issues were that generated the program. As a profession, I think we’ve lost a good bit of that. We default too frequently to simply accepting that beloved POR.

As important as that first step (empathy) was/is—we believe a greater sense of empathy based on research is necessary to be of highest value to the needs of the future. This is no longer about waiting to be told what to do. Rather, it is about researching, defining and getting ahead of the issues of importance so we can shape the programs and solutions being created.

Stepping out of our limited view of the profession, to embrace our natural ability to solve problems at a much higher and more influential level than before is our responsibility. Given the complexity of the global issues we face, we need to recognize just how much we need to step up and stop living under past paradigms.

To that end, in support of the firm’s mission and commitment to lifelong learning for all, and to advocate for so many things that are critical to the future, particularly in education, we formed a non-profit research/ consulting organization called the 9 Billion Schools Institute. Through the work of the Institute, topics around the future of how we teach and learn, how facilities need to respond to change, the role of design in enhancing productivity in the corporate world, etc., are being explored to help us shape and implement the future so others can thrive in it. In doing so we believe we add substantive value to what we provide our customers through design and execution, and we enhance the idea of what architecture can provide to society today.

We are doing this because we believe it is key to our ability to thrive in an ever more complex culture and profession. We are doing this because it is no longer good enough to design it, build it, and then just walk away. We have an obligation to understand more about what we do and its impact on the complex fabric of our world. Our designs need to be accountable to the performance goals necessary to enhance our communities and the places in which we live. To be responsible/accountable we need to know more, to understand more, and to analyze more so that we can promote the value with the proof that what we do is better for us all.

1 Friedman, Thomas L. Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist’s Guide to Thriving in the Age of

Accelerations. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

Dick Thomas, vice president at SHP, has a broad background of experience gained over his 40 years of diverse practice in the public and private institutional and commercial business markets.